Return to Normal, or the New Normal?

This past year many topics of conversation have been centered around mortgages and inflation ‘returning to normal’ after a volatile time surrounding 2020. As any economist might say, it depends. What is ‘normal’? Are we examining the past two decades? I think it is important to look back a bit farther to try and determine normalcy, more specifically, to understand the history of the Federal Reserve and how this organization plays a primary role in the bond (and mortgage) markets.

History of the Fed and How This Impacts Mortgages

The Federal Reserve (or the Fed), the central bank of the United States, plays a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s economy. These rates influence everything from consumer loans and mortgages to business investments and the health of the overall economy.

Before the creation of the Fed in 1913, the U.S. economy was marked by frequent financial panics and a lack of central authority to stabilize the monetary system. The Federal Reserve Act was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson in December of 1913 in response to these financial instability issues. The goal was to create a central institution that could manage monetary policy, act as a lender of last resort, and provide a more stable financial system. One of the key tools the Fed was granted was the ability to set interest rates, specifically the Federal Funds Rate – the rate at which banks lend to one another overnight. This Fed Funds Rate is the primary driver of all rates in the market.

In the early decades of the Fed, interest rates were often set to manage inflation and encourage or discourage borrowing (i.e. cool down the economy or stimulate it). In the years following World War I, the Fed’s interest rate policies were initially focused on controlling inflation, which had surged due to wartime spending. The Fed raised rates in the 1920’s to cool off the economy, but these policies proved ineffective in preventing the stock market crash of 1929 and onset of the Great Depression. During the Depression, the Fed made several key mistakes, especially not lowering rates aggressively enough to stimulate economic recovery. As the crisis deepened though, the Fed took a more active role in pushing rates down. These actions, alongside FDR’s New Deal, helped begin the slow process of recovery.

Post WWII, the economy saw a period of economic growth for the U.S. Having learned from the lessons of the Depression, the Fed maintained relatively low rates to support the economy. However, inflation began to creep higher in the 1960s, driven by increased government spending on the Vietnam War and social programs.

In 1971 the average interest rate on a home loan was 7.54% for a thirty-year mortgage. A decade later that average shot up to 16.64%. The 70’s brought a decade known for “stagflation” (low growth and high inflation) caused by a variety of factors: expansionary monetary policy, the oil embargo and Iranian revolution (causing a 7% decrease in the global oil supply), and unemployment reaching 9%. The decade was closed out by one of the most prominent heads of the Federal Reserve taking the chairman seat, Paul Volcker.

The 1980s brought one of the most defining periods in the Federal Reserve’s history. Volcker responded to this runaway inflation with a series of the most aggressive interest rates hikes we have ever seen. At the peak, the fed funds rate reached nearly 20% (compared to a measly 4.5% today) while the 30-year mortgage reached an all time high of 18.4%. While a recession did ensue in the early 80s, Volcker was able to achieve his goal of taming inflation by the end of the decade.

The 2007 Global Financial Crisis was probably the next largest moment for the Federal Reserve. While the banking institutions of the United States entered a crisis, Ben Bernanke, slashed interest rates from 5% to 0.25%, introducing the most aggressive Quantitative Easing Program ever seen. until 2020. This move spurred one of the longest bull markets in history and welcomed the ‘lower for longer’ view on interest rates. Mortgage rates slowly creeped down over this period from ~5% in 2010 to as low as the 3% mortgages we all saw in 2020 and 2021.

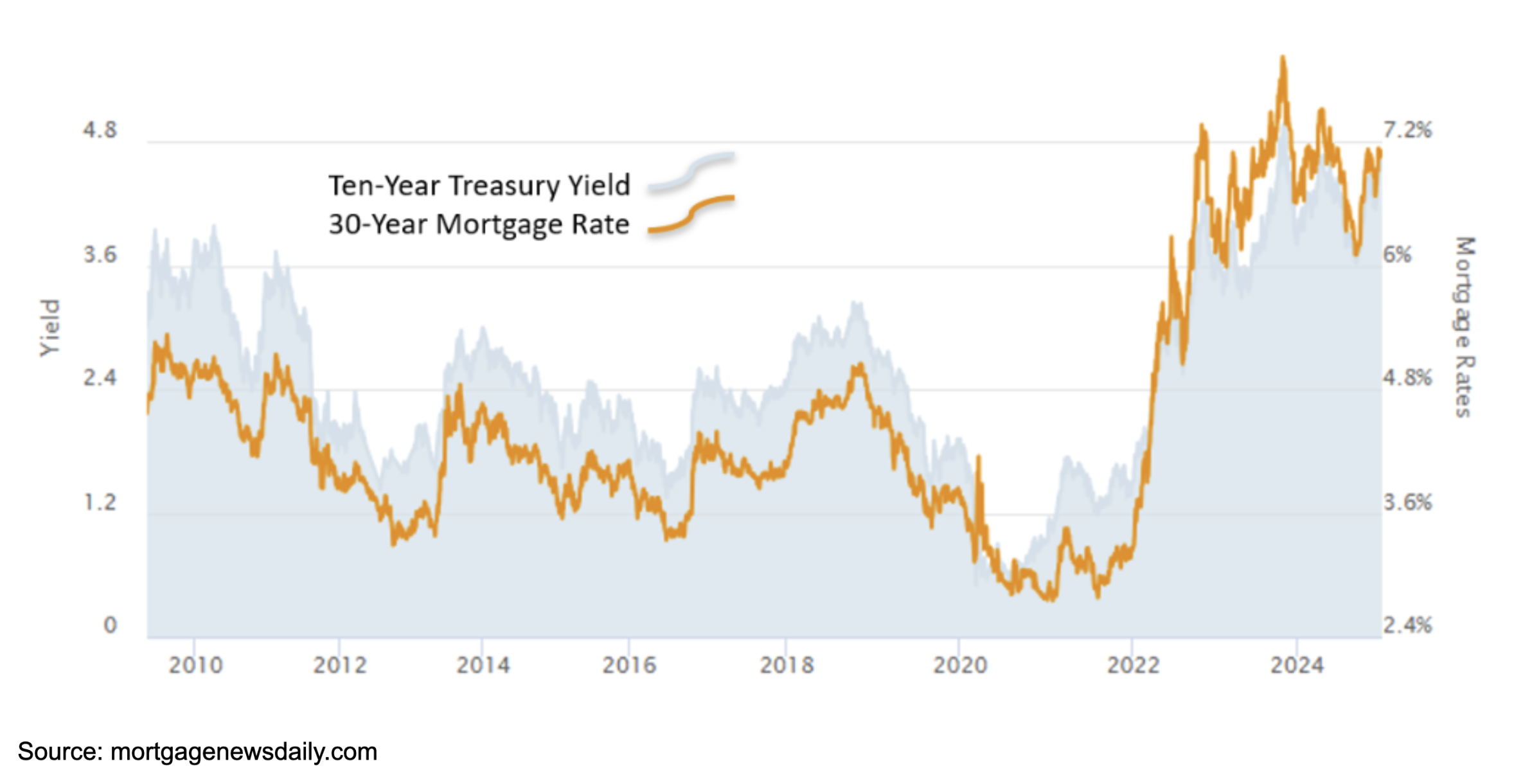

Today the average mortgage rate hovers around 7.5% as the Fed has hiked rates back up. But they cut rates at the end of 2024, so why did mortgage rates go up? The rate your bank gives you is not just pulled out of thin air, rather it historically has been tied to the ten-year treasury yield (plus ~2% premium to ‘compensate’ the bank for the risk of lending the mortgage).

The ten-year note, while following the Fed Funds Rate somewhat, still varies significantly based on, among other things, the bond market’s perception of where yields will be in the future.

Think of the Fed Funds rate as the Federal Reserve’s view of the economy, set by a board that meets to set that rate periodically, while the ten-year treasury note is the collective bond markets forward view of the economy and is adjusted in real time in the markets.

While the theory and strategy of the Federal Reserve has changed over the years, its core responsibility has not. The federal reserve has two mandates: price stability (inflation, measured by CPI) and low unemployment. They have the role of setting the base rate that banks lend between each other, which, in turn, leads to the market dynamics of longer term debt. This ‘risk free rate’ is the key base in valuing everything from stocks to real estate and rates on banking products such as mortgages.